Organized by Australia, Kyrgyzstan and the United States of America, and UNODC Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation Section, Vienna NGO Committee on Drugs and World Health Organization

14:10-14:20 Opening:

Gilberto Gerra, Chief, Drug Prevention and Health Branch, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

We are going to present the results of our work on peer distribution of naloxone . Frankly, it is unveliavable that we have to fight for Naloxone, as this is a medication that has no controled substance. Stigma associated with opioid use disorders is so potent that it extends to naloxone itself. This is really unbelievable.

Vladimir Poznyak, Unit Head, Alcohol, Drugs and Addictive Behaviours, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization (WHO)

I would like to call your attention to the fact that the research showcased by this event also serves as an assessment of the WHO’s own Guidelines on Community Management of Overdose Overdose.

There is no time to wait. Every day, week, year of inaction means that persons are dying due to opioid overdose when there are medicines that could save their lives.

14:20-14:35 UNODC-WHO multi-site study on community management of opioid overdose, including emergency naloxone – Findings from the feasibility study

Prof Paul Dietze, Program Director, Behaviours and Health Risks, Burnet Institute, Australia

Opioid overdose is a major public health issue. These deaths are preventable because we have an opioid reversal medicine called naloxone.

There has been a large range of initiatives to develop programmes of peer disstribution of Take Home Naloxone, with the main document being the WHO Guidelines on Community Management of Opioid Overdoses.

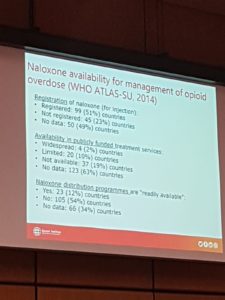

Naloxone is officially registered as a medicine across 51% of all countries, but most countries don’t provide data on the availabilit of Naloxne. The break down of naloxone availability across the world as follows:

The WHO-UNODC S.O.S. programme (S.O.S. for Stop Overdose Safely) is a peer-distribution programme in which we attempt to provide take home naloxone to likely witnesses of overdoses. The goal at the launch of the SOS Initiative in March 2017 was to have 90% of those likely to witness an overdose are trained to implement Naloxone; 90% of those trained to provide naloxone are provided with a supply; and having 90% of provided with Naloxone are actually carrying it with them.

The programme involves a training cascade, in which there are three levels of training. From Level I, in which national master-trainers are being trained, to Level III in which potential overdose witnesses are trained. This programme was rolled out in Kyrgyztan, Kazakhstan Taijikistan and Ukraine, and the goal was to train 15,000 potential witnesses.

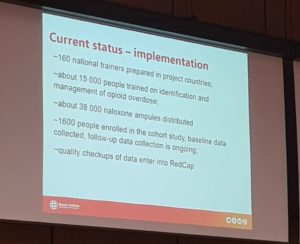

The current status of implementation of the SOS in these four countries is provided in the following slide:

It’s incredible that we were able to gather 1,600 people for the cohort of trained persons that are used to see what is the impact of the programme.

As for the results, I’m happy to release them today here. There were three key questions:

(1) Who participated in the study?

The majority of people who were part of the study were people who used drugs. As for the people within this category, 95% had previously injected drugs, and 40% had experience food scarcity recently. 93% had witnessed overdose before. The people who use drugs were also more competent in using the Naloxone than people do not use drugs.

(2) What was the impact of the training?

The fundamental finding is that training worked. There was in all cases a significant improvement on the reported skills and competence of the people who had gone through the training.

(3) Do trainees use naloxone at witnessed overdoses

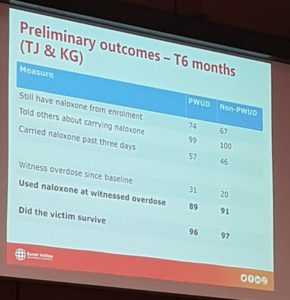

The results of the programme can be found in the following chart:

The preliminary outcomes after 6 months (only in Kyrgyztan and Taijikistan) is that around 74% of people who use drugs that had received training had stlll received the naloxone from enrolment, 31% said they had witnessed at least an overdose since the baseline training, and 90% of them said that they had used naloxone at the witnessed overdose. In almost all cases, the victim survived. The rates for cohort members who do not use drugs were broadly similar.

Furtermore, almost 89% of all the people who used drugs who went through the training reported that they used drugs more safely since the training.

Conclusion

Take Home Naloxnone can be implemented at scale using the SoS methodology, in a way that it is actually effective.

14:35-14:40 Mara Burr, Director, Multilateral Relations, Office of Global Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, United States of America

We are proud to having funded this project. We a the US continue to witness an unprocedented opioid overdose crisis. We are committed to develop a strategy to use the abilit of communities to provide overdose-reversing drugs like Naloxone. Studies show that Naloxone is effective in reversing overdose and saving lives.

In April 2018, the US Surgen General emphasised the important of access to naloxone for several groups of people (individuals using illict opioids, individuals using opioids within the legal system, families, etc.).

Thanks to this, many people in the US can go to a pharmacy to use Take Home Naloxone.

We are making progress. 380% increase in the quantiity of Naloxone used in the USA. There has also been an over 4% drop in the rate of overdose deaths in 2018 compared to 2017, the first time this happens in many years. We will continue doing this work.

Pharmacists and health-care providers should monitor patients at risk of overdose in order to prescribe and provide Naloxone. We recognise that cost if a barrier and are working with suppliers to reduce out-of-pocket costs. There is still a long way to go though.

Timur Usakov – Perment representation of the Kyrgyz Republic, Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan there is an acute problem of opioid overdose. In order to reduce mortality we need to work on partnerships between NGOs and public authorities. The SOS programme has been a good example of it.

We had more thant 3,000 overdose witnesses trained, of which 40% were women. This programme has resulted in a decrease in the number of overdoses in the country.

14:50-14:55 Dr Allison Jones, A/g Assistant Secretary, Alcohol Tobacco and Other Drugs Branch, Population Health and Sport Division, Australian Government Department of Health

Today I’d like to share the Australian experience in opiod harm, and our experience in using take home naloxone.

Problematic opiid use has increased significantly in many countries, such as the US, Sweden, Norway. Australia in fact has seen a decrease in deaths related to natural and semi-syntehetic opioids over the last two years, but still 3 people die of opioid overdose every day.

Opioid has contributed to around two thirds of drug-related deaths in Australia. These were unintentionally overdoses of middle-aged men after mixing pharmaceutical opioids with other substances. People in rural rural areas are more likely to die of overdothes. Accidental deaths resulting from fentanyl use are relatively rare.

Australia’s pilot for the Take Home Naloxne started in December 2019 and will run through Feburary 2021. Naloxone will be available for free to people who are likely to experience or witness an opioid overdose. No prescription will be required. Each state will decide in which naloxone will be available, including pharmacies, alcohol and drug treatment centres, and needle and syringe programmes.

Another meaasures is that we have created a Real Time Prescription Monitoring system that can be used in ensuring that opioids are prescriped in the right circumstances and the right amount, and that are not over-prescribed.

14:55-15:00 Penny Hill, Harm Reduction Australia, Vienna NGO Committee

Working with civil society is key to effectively implement harm reduction programmes.

Harm reduction is one of the three key pillar of Australia’s drug strategy. Australia has been historically a leader in harm reduction, but we feel that lastly support by the government has weaked in the last years. We urge the government of Australia to reverse this trend.

Partnerships between governments and peer organisations have been incredibly important. We are very pleased by Australia e,bracing take home naloxne, and for recent decisions. Currently in most Australian jurisdictions harm rediction practitioners can train persons in using naloxone, but cannot distribute it. But we know that peer-distribution is the most effective way to ensure access to naloxone.

The implementeation of the RTPM might result in restrictions in the distribution of relevant medicines, unless appropriate safeguards are put in place. Naloxone distribution must also be available through prisons and in all support programmes. Unique programmes such as innovative peer-led overdose prevention sites, drug checking, should be implemented nationally.

My message to member states across the globe is to work with peer-led organisations. Civil society come to the CND exactly for this reason. Please do engage with them.

Vladimir Poznyak, Unit Head, Alcohol, Drugs and Addictive Behaviours, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization (WHO)

To conclude the event, let me say that opioid overdoses are the most common form of drug-related deaths, and we are clearly not doing enough globally to confront them.