Organized by the Norwegian Association for Humane Drug Policies with the support of Norway, and the Drug Policy Alliance, the International Drug Policy Consortium, NoBox Philippines, Release, and StreetLawPH.

Thursday, 15th April 2021, 10:00 – 10:50 (CET – Vienna) Co-sponsored by Norway, the Norwegian Association for Humane Drug Policies, Drug Policy Alliance, IDPC, NoBox Philippines, Release and StreetLaw PH The systematic policing and criminalisation of people involved in drug offences has had devastating impacts on the human rights of people in situations of vulnerability (especially for people who use drugs, subsistence farmers involved in illicit crop cultivation, women, young people, ethnic minorities, people facing economic hardship), health outcomes and prison overcrowding. These harms have been exacerbated in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a result of the policies established to curb infection rates. This side event will highlight some of the most pressing harms associated with policing and criminalisation, and propose a number of options for criminal justice and drug policy reform grounded in social justice, racial justice and human rights.

Moderator: H.E. Ambassador Kjersti E. Andersen, Permanent Representative of Norway to the UN in Vienna

There has been a change in Norway from punitive measures to include PWUD and civil society in decision making. 2015 – drug reform became official policy in Norway.

Committees starting point – punishment is the most severe response – criminalisation is only suitable if it reduces harm. No good evidence of criminalisation as a deterrent. Criminalisation has unintended and adverse effects. No evidence of decriminalisation increasing use of illicit drugs. Drug use better countered with health measures. This is the baseline of our drug policy and provides the backdrop to our seminar today.

Panellists:

- Lee Edson P. Yarcia, NoBox Philippines

[Video] – Criminalisation and policing for PWUD – aspiration to recognise genuine reform. Drugs play a meaningful role in the lives of people in the Philippines. Drug use figures in everyday live – methamphetamine for workers to those working overnight of for long hours – feel warm. Marijuana plays same role of alcohol in some contexts. Dominant social legal order doesn’t recognise way of life. Drug conventions create prohibitive environment. Countries invested in medicalised approach to treat people causes problems. Extrajudicial killings occur in the Philippines. Blinds many states from the reality that abstinence pushes people away and leads to risky situations and blood-borne viruses (BBVs). Philippines jails 500% over congested. Rehab centres strip people of autonomy, take away rights. Medical prohibition – people continue to use drugs. Time to accept the fact that drugs play important roles in people’s lives. Enforcement models cause more harm than good. Wide range of services is needed. We work with partners. 87% of PWUD are non-problematic – focus should be on health. Decriminalize and take people out of jails. Drugs issues are a social phenomenon. Economic emancipation is needed. Full and productive employment is needed. Addressing poverty is needed. Decriminalised interventions. Compulsory detention centres have no place in drug policy framework, should be a priority of the government. Health is key, comprehensive health services for HIV prevention and acre needs. Access to sterile injecting equipment and essential health services is necessary. Fatal overdoses and BBVs – drug related deaths will occur. Genuine health approach based in harm reduction. Harm reduction dispels archaic belief that abstinence is the goal. Drugs play a meaningful role in people’s lives. Prohibitive environment exists. It’s time to decriminalise drug use. Humanity is key.

- Theshia Naidoo, Drug Policy Alliance (United States)

Will cover: harms associated with decision to use criminal justice system, recent reform adopted in the state of Oregon. I will focus on US.

More people arrested for drug possession than any other criminal offence. Often black, indigenous, other communities of colour, consequences of arrest very severe. In terms of health aspects – high overdose rates in US. Decision to use/not use substances, and overdose rates, don’t rise and fall as a result of drug policies. System of punishment and arrest is invested in, we don’t see investment in harm reduction and treatment. The state of Oregon has high overdose rates and incarceration rates. Oregon Measure 110: successful ballot initiative in 2020 – eliminates possession penalties and promotes harm reduction. The victory made Oregon the first state in the US to take a major step towards dismantling the system of criminalisation and punishment that has disproportionately harmed communities of colour. Voter enacted reform – victory makes Oregon the first state to take step forward to dismantle system.

Measure created the Drug Treatment and Recovery Services Fund, funded by existing revenues: marijuana taxes in excess of $45 million when Act takes effect. Only took effect on Feb 1st – too soon to have data. Criminalisation Commission did a study on the racial impact – should reduce disparities. Racial disparities in every step of processes.

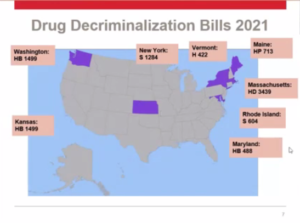

Number of states introducing legislation on decriminalisation. This is unconstitutional. Last few years – decriminalisation was an issue discussed among advocates, but now we see Oregon trying something different – there are now bills pending in each state above.

- Adrià Cots Fernández, International Drug Policy Consortium

Going to present the findings of 2 recent IDPC reports –

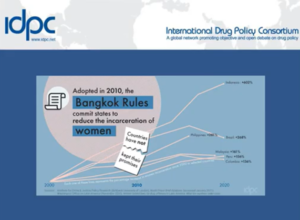

- “Punitive Drug Laws: 10 years undermining the Bangkok Rules”

- “Prisons and COVID 19: Lessons from an ongoing crisis” – 4 national case studies on how punitive national frameworks have affected peoples health.

Both reports reach a common conclusion – any effort to advance gender equality, promote health needs to include reforming drug policies. If not, it will be undermined by punitive drug laws.

Global female prison pop has grown 3x as fast as that of men. PNI: number of women increased by 50% in Asia and 19% in South America in last 20 years. Not equal across regions. Decreased by 29% in Europe.

Explanation: due to drug laws. Brutal and draconian drug laws introduced. Increase in penalties was followed by an increase in incarcerations. 62% of women incarcerated for drug related offences compared to 25% of men. In 2018, the UN estimated that 35% worldwide of women were incarceration for drug offences compared to 19% of men.

Unheard lessons of the Bangkok Rules for Drug policies:

3 key principles emerged that could be basis of criminal justice reform.

- Prisons should be a measure of last resort: through non-custodial measures at all stages of the process. Alternatives to conviction include diversion, early release of all women – as committed to in Bangkok Rules. Reasons that women take part in drug trade are poverty, caring responsibilities, some cases coercion. These factors won’t be adequately addressed in prison. Women have less access to legal counsel and money.

- Pay attention to personal circumstances: through mitigating factors. As written in Bangkok Rules. Mitigating factors can include history of drug dependence, poverty, disability, low level involvement in drug trade. In practice there are high minimum charges for drug related offences. Personal background is usually disregarded.

- Avoid a gender-blind approach: consider the specific needs and circumstances of women. Impact of drug policies is not gender blind – and responses should not be either.

Decarceration and COVID 19

- 535,000 tested positive, +3900 deaths in prisons worldwide due to COVID – probably an underestimate

- HRI estimated that total prison population has only dropped by 6% during COVID – disappointing

- The arbitrary exclusion of drug offences from those released.

- A “lockdown within a lockdown” – reduced access to health. Isolation from mental health and drug services for over 10 months. Social workers in some instances could only call through video conferencing.

- Isolation from family and close relationships due to limits on visits during COVID. Isolated from main source of essential goods in Sth America. Women provided with only one pack of menstrual pads over the course of three months.

- Isolation from judicial proceedings

Recommendations:

- Ensure that prisons are the exception, not the rule

- Ensure access to gender-sensitive health care including AOD and mental health services

- Provide support to formerly incarcerated people

- Decriminalise PWUD

Prison is not an appropriate or effective place to address the reasons for drug involvement: poverty, marginalisation and lack of opportunities. Prison is also not a just response.

- Arild Knutsen, Norwegian Association for Humane Drug Policies

Norway is in the midst of drug policy reform – still don’t know what final result will be – remarkable that our conservative country has taken this step. How did we get to governmental proposal to decriminalise? Because of the harm reduction in Norway and giving people with drug addiction patient rights – reform in 2004. In the 1990s we introduced NSPs, and 2005 opened SIF. Drug user organisations established. Access to methadone. On one side we help, on the other we criminalised. The health centred approach brought evidence on what worked and what didn’t. We are a drug user organisation established in 2006. We promote OST, harm reduction, oppose criminalisation. We have a high media profile and meet our critics with upmost respect. Some politicians wanted us to only work in the health care system, but nothing about us without us, we are also a political force. We are not criminals because we use drugs, and we are not patients because we use drugs – first, we are citizens. We have patient rights, but also human rights. Criminalization doesn’t prevent drug use – just creates stigmatisation. It’s actively counterproductive – many people don’t seek help. While we are criminalised, the health centered approach and its benefits is narrowed. In 2006, we wrote a article in Norway’s’ biggest newspapers, and gained many supporters for human rights to be written into our drug policies. By 2017, many politicians encouraged a move from criminalisation to health. In 2019, the committee suggested a decriminalisation model. Framework exists – police still involved but can move from punitive to supportive approach. Well received by WHO, OHCHR. Parliament will vote over proposal in June – we still don’t know how it will turn out. Civil society recognised as driving force of this reform. We hope other countries follow this example and include PWUD in models of reform.

Moderator: H.E. Ambassador Kjersti E. Andersen, Permanent Representative of Norway to the UN in Vienna

Q&A:

Q, for Arild: Where are the challenges now – how will you approach this?

A: it’s hard for many to understand that punishment doesn’t stop people using drugs. Have to have a good debate about this – but this report clearly states this, that punishment creates more crime and marginalises, and results in overdoses. Hope that the majority of parliament votes for this.

Q, for Lee: If you were to speak about immediate challenges, what would they be and how would you find solutions?

A: First – direction for legislative reforms. Movement to create a more c=punitive environment in the Philippines and a reintroduction of the death penalty for drug offences. Really important challenge to monitor. But there are spaces to push for reform – some of the bills focus on more public health approaches. UN Technical Assistance – not a challenge but important opportunity. If we can reform, that would be an important success for us. This is a space for international communities to help us push for reform.

Q, for Arild: How do the top gov officials in Norway see drug offences?

A: Seen as a criminal issue, but authorities are now seeing it more as a medical issue. As we know, it’s only a small amount of PWUD who are sick, and this is starting to be recognised.

Q, for Lee: How do you advocate in the Philippines and stay safe? How has COVID affected this?

A: For safety – we work in numbers. We broaden civil society network and work in groups – try to collaborate and engage others. Human rights defenders have it more difficult – we have more opportunities in drug reform to engage government. COVID did restrict our work – problem for women incarcerated and pregnant women – greatly impacted by COVID. Has made our work more urgent to bring people out of prison.

Q: Decriminalisation alone will not solve the problem – are there any safe supply initiatives?

A (Adria): Yes, of course – across the world there is advocacy for safe supply -mostly on cannabis but not only. Big movement in US and South America, also Europe. These initiatives should not be separate from decimalisation – it should all be implemented together at the same time.