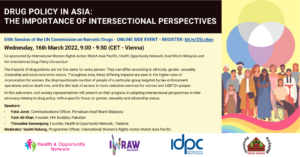

Organized by the International Women’s Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific with the support of the Health and Opportunity Network, the International Drug Policy Consortium, and the Persatuan Insaf Murni Malaysia

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6WrkilXc9cU&w=560&h=315]

The impacts of drug policies are not the same for every person. They can differ according to ethnicity, gender, sexuality, citizenship and socio-economic status. Throughout Asia, these different impacts are seen in the higher rates of incarceration for women, the disproportionate number of people of a particular group targeted by law enforcement operations and on death row, and the dire lack of access to harm reduction services for women and LGBTQ+ people.

At this side event, civil society representative will present on their progress in adopting intersectional perspectives in their advocacy relating to drug policy, with a specific focus on gender, sexuality and citizenship status.

Gloria Lai, International Drug Policy Consortium: Welcome everyone to this side event at the 65th session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs. Before we start, we would like to refer to the massive human rights, humanitarian, and displacement crisis that is happening in Ukraine. Harm reduction and HIV prevention services are courageously trying to continue their work and ensure the continuation of services to people in the country. However, just like the humanitarian support gathered by communities around the world, the supplies from harm reduction organisations are not able to reach all the organizations and people who need it, because the humanitarian corridors are not working. We urge the governments and international community to use their power to ensure the humanitarian corridors inside Ukraine.

Moderator: Vashti Rebong, Programme Officer, International Women’s Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific: My name is Vashti and I will be moderating our discussion today. I work at IWRAW AP, which stands for International Womens Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific. We are pleased to be co-organising this side event together with other civil society organisations that advocate for intersectional approaches to drug policy: the International Drug Policy Consortium, Insaf Murni in Malaysia and the Health Opportunity Network in Thailand. We are so honoured to have 3 outstanding advocates from Asia speaking on our panel today: Yatie Jonet from Malaysia, Yasir Ali Khan from Pakistan and Thissadee Sawangying from Thailand. I will introduce each of them in a bit more detail, right before I invite them to speak. Understanding intersectionality and how to apply it to advocacy for gender equality and human rights is a priority for IWRAW AP. Specifically, intersectionality allows us to see how different aspects of a person’s gender, social and political identities overlap with each other, and to understand how this may result in an individual experiencing multiple and complicated forms of oppression and/or privilege. To start our panel discussion on the connections between intersectionality and drug policy in Asia, I invite Yatie to take the floor. Yatie works as a communications officer for an NGO called ‘Insaf Murni’ offering care services for people in different situations of vulnerability, including women and transgender women who use drugs, in Malaysia. She is a long-time advocate for harm reduction and human rights for women who use drugs. Yatie, the ‘stage’ is yours.

Yatie Jonet, Communications Officer, Persatuan Insaf Murni Malaysia

I am a Communications Officer working with Persatuan Insaf Murni Malaysia on issues relating to the vulnerabilities of women who use drugs in Malaysia. I am a life-long advocate for human rights and harm reduction. Today I will speak about ‘Intersecting Identities and Drug Use: Speak for Drug Policy Change’. We call upon our governments to reform drug policies. The INSPIRE project in Malaysia – focussed on empowerment of women and transgender women – builds resilience, trains peers, and promotes drug policy reforms. It is a three-year project, and we have run focus group discussions and interviews with women who use drugs, transgender people, sex workers, spouses of people who use drugs, youth who use drugs, and youths with parents who use drugs.

I will now present some stories from our interviews and focus group discussions, covering the intersectional perspectives that really need to be addressed urgently. The first group – women who use drugs – showed how women are easy targets of law enforcement and misuse of power, and punitive drug policies result in women who use drugs being separated from their children. There was a story of a woman who uses drugs being stopped at roadblock, had a clear urine test, but was charged with possession due to previous charges and lost access to methadone.

The second group was transgender women: there are no drug treatment services specific for this population in Malaysia – there are uncertainties with whether to provide treatment as part of men’s or women’s services – there is no action taken to find a solution.

The third group were spouses of people who use drugs: they had multiple identities: a wife, mother and drug user – they spoke of themselves as a ‘functional drug user’. One story was of a person’s husband being arrested and detained, but not provided any details of where he was.

The fourth group we spoke to were youth who use drugs: there is an unmet need for family and institutional support. Some people can’t find work and have to rely on their families. There are also conflicting views amongst the youth: false perceptions on the role of prison/detention centres – narratives are starting to change here though as youth who use drugs speak more about the number of times they had been in prison and rehab.

In conclusion: intersectionality of gender, poverty, age, and drug use sheds light on how drug policies have impacted women, transgender and young people in Malaysia. The stories we are telling call for action for drug policy change, especially to remove practices that are harmful to PWUD and their families. There is an urgent call to reform punitive laws

Moderator: Vashti Rebong: Thank you Yatie for sharing about the impacts of drug policy on women and transgender women who use drugs, and the importance of taking an intersectional approach and the empowerment framework to drug policy. Our next speaker is from Pakistan: Yasir Ali Khan, who is the Founder of a civil society organisation called HIV Buddies that offers help on prevention and treatment of HIV, as well as on drug use issues. Yasir, you have the virtual stage.

Yasir Ali Khan, Founder, HIV Buddies, Pakistan

We work with MSM and trans communities, injecting communities, and non-injecting communities. In Pakistan, there are no support programs, criminalisation, no OST (people are suffering), and no support for people in relation to SOGIE (sexual orientation, gender identity or expression) issues. There is a lot of use of stimulant drugs, and injecting drug use, including in the context of chemsex. There is a need to help people come out of their addiction.

We worked on a recent situational analysis for UNDP Pakistan on substance use, which outlined the major issues faced by the community: discrimination, harassment, anxiety, loneliness, stigma, discrimination, easy target, helplessness. For the research to inform this situational analysis, we interviewed 689 people – 256 online – we did 63 desk reviews with people who couldn’t read or write, in-depth interviews with 10 people living with HIV and 10 with people who were HIV negative,

The stories from the community showed the different responses to chemsex: it makes me happy and satisfied / I lost my job due to chemsex / difficult facing stigma and discrimination. Amongst them, there were also fears of being criminalised, arrested by police, losing employment, mental health concerns, physical health concerns, physical violence and blackmail.

Moderator: Vashti Rebong, Thank you Yasir for shining a light on issues relating to drug use and SOGIE in Pakistan. You make a powerful case on the need for policymakers to adopt intersectional perspectives in order to develop the most appropriate policy responses to drugs. Our third and final speaker on the panel is Thissadee Sawangying from Thailand. She is the founder of the Health & Opportunity Network in Thailand, which engages in advocacy and provides care services for LGBTQI+ people and sex workers who use drugs. Thissadee, please take the ‘virtual stage’.

Thissadee Sawangying, Founder, Health & Opportunity Network, Thailand

First of all, I would like to say thank you to all the partners and for the great opportunity for me to talk about drugs and intersectionality. The first thing I would like us all to have a common understanding about is that drugs are made illegal and a threat against national security in Thailand. Therefore, the country initiated the war on drugs and imposed severe penalties on those involved in drug related activities. It has resulted in massive prison overcrowding and many other problems.

Being a person who uses drugs or involved in any other drug related activities in Thailand means you are defined as a criminal, a bad person. These narratives and perceptions stigmatise people involved with drugs and are continually reproduced. For that reason, since the war on drugs began, we have had to fight against stigmatisation, demoralisation, discrimination and human rights abuses. Over the past 20 years, advocacy on drug issues in the country has focused on reducing HIV prevalence which has received continuous support from the Global Fund. However references to harm reduction focus on people who inject drugs.

In the context of the city of Pattaya where the Health Opportunity Network is based, we started working with trans women on preventing the spread of HIV while incorporating dimensions to address their marginalisation and the need for gender diversity. Pattaya is a paradise for trans women. Many of them have similar stories: a “son” who fled from home in the countryside where they were not accepted by their family, a “son” whose gender doesn’t match their biological sex, a “son” who doesn’t live up to the expectation of their family, community, and society. But at the same time, Pattaya is not a paradise for everyone. It is a city of colourful night life, crime, and drugs, just like any other city. We started working on gender, health and HIV/AIDS issues because of the lack of access to treatment after the war on drugs started 20 years ago. It affected the quality of life for many people, and led to the loss of life, violence and human rights violations. We then started to take interest in working seriously on drug issues with an intersectional approach, which affects our friends’ way of life, health, and access to treatment.

We started with working on HIV issues, where the only thing we understood about drug use is that it significantly affects the antiretroviral therapy (ART) process, and was a factor in some people leaving the treatment programme. We working to improve our understanding about drug issues by having focus group discussions with trans women who use drugs in Pattaya. Their stories about their first-hand experiences allowed us to learn more about their drug use patterns, background and the connection with their trans identity as well as livelihood in Pattaya. Many of them worked as a showgirl, bartender, go-go dancer or sex work. We now understand that their ART process was disrupted when they were arrested for drug use. Also, they were afraid that their identities as a person who uses drugs and living with HIV would become known and they would be stigmatised.

Drugs often don’t cause harm, but the harm is caused from the law enforcement and criminal justice processes, and other people in authority. The community of trans women who use drugs shared with us that they have experienced extortion, torture, forced labor, sexual harassment, arbitrary detention, and even lost their friends during their interactions with law enforcement and in the criminal justice process. Being trans women, with other intersectional identities such as also being a sex worker – both identities that are not socially or legally accepted – they suffer high levels of stigmatisation and discrimination and it’s hard for them to gain acceptance from society. And even more so when they overlap with other marginalised identities such as people living with HIV or migrant workers. As people who use drugs, they are seen as evil, as criminals who have to be arrested. Often, even after they have served their sentence, they will be jobless, then homeless – a cycle, living without human dignity in the land where LGBTQ+ people supposedly call paradise.

Stigmatisation and discrimination from society and governmental services also intensify the degree of oppression. Being trans with breasts and long hair but not having gone through the transition process – when they are sick and get admitted into hospital, which ward should they go into? Female or male? When they are imprisoned, which jail should they go to? Female or male? – The services, policies, and laws that only consider the binary gender system has become an issue people started to discuss. However there are still no structural reforms.

For transgender people, sex workers, migrant workers, people living with HIV, people who use drugs, homeless people—which institution is responsible for caring for them? Even with Global Fund programmes where they differentiate key populations into MSM, PWID, migrants, and so on, transgender people who use drugs are not included. These are the people who are left behind, and help us to see the importance of taking an intersectional approach to responding to issues such as drug use. Thank you.

Moderator: Vashti Rebong: Thank you Thissadee so opening our eyes to the experiences of some transgender people who use drugs in Thailand, and how they experience the impacts of drug policies there. Taking an intersectional perspective helps to identify the layers of challenges and discrimination they face in trying to reach better outcomes for health and human rights. It appears that one of the next steps required would be ensuring the meaningful engagement of transgender people who use drugs in developing appropriate policies on drug use and dependence. We now turn to addressing questions from the audience.

Question: have people reported not accessing health services due to fear of arrest?

Yatie: no formal reports other than being turned away. Living in very repressive environment where punitive laws have given a green light to arrest people who use drugs, let alone improving access to health services. Government assistance is not available for each citizen due to the repressive drug policy environment. During the pandemic, I couldn’t go out to buy groceries due to road blocks as I would be tested for drug use.

Yasir: we need to work together on these issues – doesn’t matter if someone wants to be female or male. We are working for humanity and raising the voices of affected communities, calling for government responses that support, don’t punish. I have one request – help people who are suffering with drug dependence – they are not criminals, we need to love them back to life.

Moderator: Vashti Rebong Thank you so much to all our speakers and all of your who were able to join our event today. We hope that you can also join us in continuing to work towards acknowledging, understanding and incorporating intersectionality, particularly in the reform of drug policies that are in line with principles on human rights and harm reduction. Thank you.