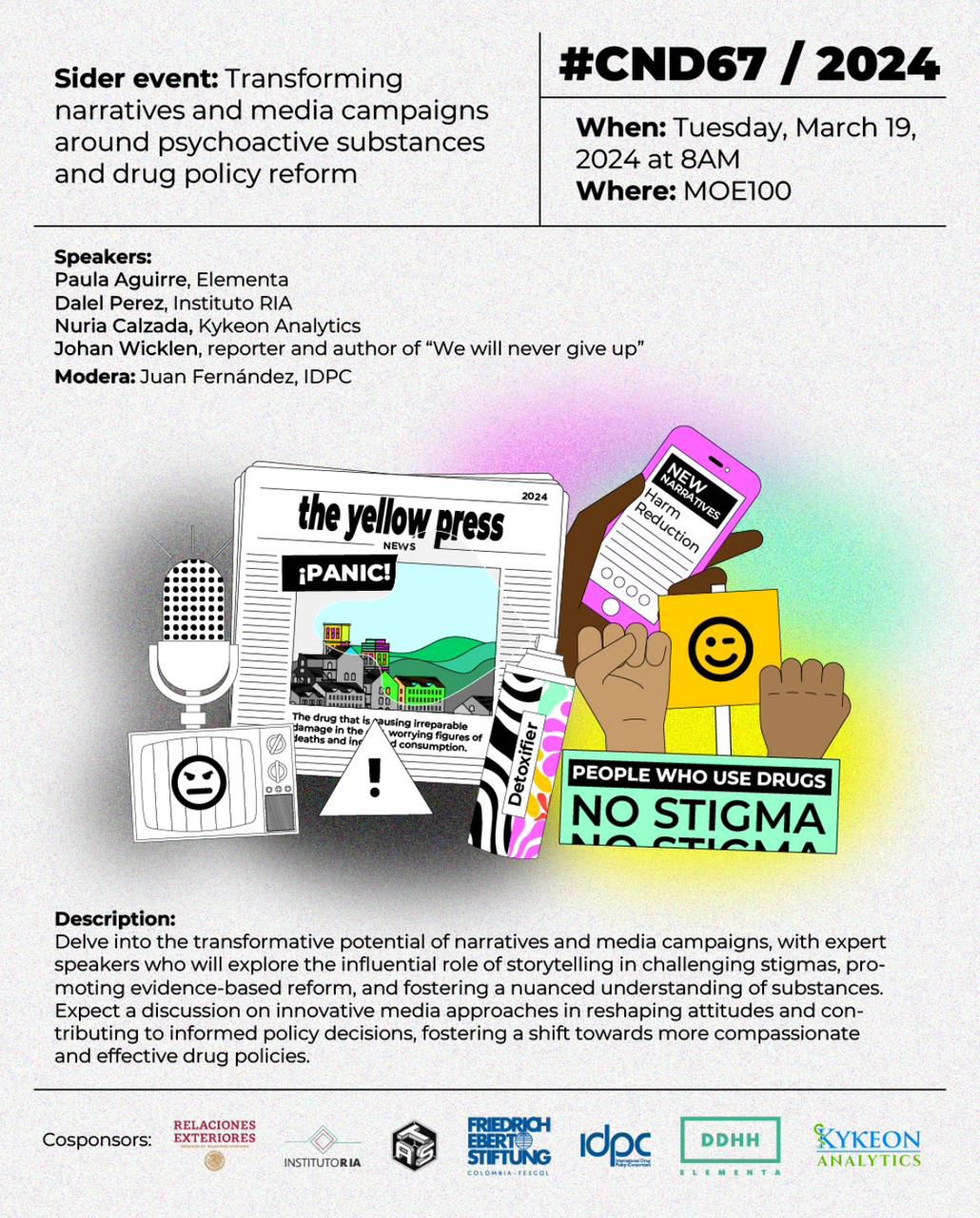

Organized by the Instituto RIA with the support of Mexico, Acción Técnica Social, Elementa DDHH, the Frederich Ebert Stiftung Institute, the International Drug Policy Consortium and Kykeon Analytics

Tuesday 19th March 2024 – 08:10-09:00, MOE100

Panellists:

Paula Aguirre – Elementa DDHH

Dalel Perez – Instituto RIA

Nuria Calzada – Kykeon Analytics

Johan Wicklen – Reporter and author of “We Will Never Give Up”

Gloria Miranda- Directorate for Drug Policy, Ministry of Justice of Colombia

Chair: Juan Fernandez – International Drug Policy Consortium

Event Recording

Chair: Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Before we begin, I want to express solidarity with the people of Palestine and those in Gaza as they confront an unprecedented humanitarian catastrophe. I urge everyone in this room to contribute to ending this situation through the implementation of an immediate, permanent ceasefire and credible commitments towards sustainable peace and justice. I’m Juan Fernandez Ochoa, I’m the Campaigns and Communications Officer at IDPC which is a network of a 195 organisations in 75 countries united in the belief that drug policies can and should advance social justice and human rights. I’m really grateful to Instituto RIA for organising this event in collaboration with Acción Técnica Social, Kykeon Analytics, Frederich Ebert Stiftung foundation, Elementa, and the government of Mexico. Last Thursday, at the opening of the 67th session, Thursday morning, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights highlighted the serious human rights consequences of the war on drugs and the need for transformative approaches that prioritise health and rights at the centre in drug policy making. Beyond formal norms and policies, narratives, discourses, and media representations also play a crucial role in the dehumanisation of people who use drugs and those perceived as associated with drug markets. This event presents an excellent opportunity to explore how we can pursue redress and repair, also through these means. To support us in navigating this question, we have a wonderful panel of experts: Gloria Miranda, a historian with an option in political science, Master Cum Laude in peace building from the University of Los Andes, with a specialisiation in economics and currently responsible for drug policy the with the government in Colombia, Paula Aguirre, a lawyer with experience in human rights, transitional justice and drug policy; Paula is the Director of the Elementa office in Colombia. We have Nuria Calzada, who coordinates the drug policy area of Kykeon Analytics, has been active in harm and risk reduction for over 20 years, and wrote a helpful guide for reporting on drugs; ; Dalel Perez, a sociologist with experience in Latin American studies, who collaborates with Instituto RIA —a research and advocacy organisation in Mexico; and, Johan Wicklen —who works as a news reporter at the Swedish public service broadcasting company SVT —and who in 2022 released his debut book ‘We will never surrender – How Sweden lost the ‘war on drugs’ With limited time, let’s dive into our discussion, starting with Paula. Elementa has launched the detoxing narratives project, focusing on de-stigmatisation at its core, and recently produced a report on combating prejudice against women in relation to drugs. It would be fantastic to hear more about this project, its intentions, goals, and achievements. We have a lot to go through so let’s dive right in!

Paula Aguirre – Elementa DDHH: Our focus at Elementa has been on the detrimental effects that prevailing drug policy narratives have on public discourse and, by extension, on the lives of countless individuals, especially in countries like Colombia where the illicit drug market has exacerbatedand fueled internal conflict. Media narratives, often echoing prohibitionist strategies, lack scientific evidence and are riddled with stigma. These narratives not only validate ineffective approaches but also contribute to a negative impact on thousands of lives. Elementa has embarked on a project to shift these narratives towards less toxic and more analytical discourse. This initiative, aimed at detoxifying public debate, proposes a different approach to handling information on drug policy in media. When we initiated this project, our comprehensive review of news, publications, press releases, and opinion columns revealed a landscape dominated by toxic narratives. Our findings were alarming, to say the least, demonstrating a widespread need for narrative change across various sectors, including the media, academia, congress, and even within civil society. This endeavour has grown into a concerted effort to educate as many people as possible. Through our social networks and website, we continually update information, highlight instances of toxic narratives, and importantly, we provide guidance on adopting more constructive discourse and practices. We believe it’s not sufficient to merely point out the flaws; we aim to illustrate the right approach to discussing drug policy. Let me share two instances that underscore the necessity of our work. During legislative debates on drug policy in Colombia, it’s not uncommon for discussions to veer off into sensationalism. For example, a congresswoman inaccurately spoke about cocaine cultivation instead of coca crops, aiming to stir fear/misinform rather than inform – and unfortunately succeeded. Predictably, her misleading statement became the headline, illustrating the need for our detoxifying efforts.On a positive note, Colombia’s new drug policy deserves commendation for its progressive stance. It acknowledges the harmful effects of prohibition on vulnerable populations and introduces a cross-cutting axis in both national and international drug policy of Colombia. This approach seeks to transform perceptions towards drug use, emphasizing the need for a change in narrative and approach. As we navigate the complexities of drug policy and public discourse, Elementa’s mission is to pave the way for more informed, compassionate conversations. By challenging and changing the narratives, we hope to contribute to a drug policy that is rooted in human rights and social justice, marking a significant step towards peacebuilding in Colombia and beyond.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Chair: Thank you, Paula, for that enlightening presentation. You’ve given us plenty to consider, especially regarding the collective responsibility we share, including the role of satellite platforms, in detoxifying narratives around psychoactive substances and drug policy reform. Nuria, your work is particularly notable; you’ve been engaging in conversations not just back home in Spain but worldwide, with a wide range of advocates, civil society and individuals resisting prohibition. You’ve adeptly navigated the intersection of advocacy and journalism, providing a platform for those voices/advocates often side lined in these discussions. It would be immensely valuable to hear more about your experiences and insights, especially how you’ve observed the unintended effects of moral panics, the language used to dehumanize those involved, and your perspective on the erosion of the mainstream, hegemonic approach to drug policy reporting. Thank you once again for such a comprehensive overview and for the depth of engagement you’ve shown in this vital area.

Nuria Calzada – Kykeon Analytics: Thank you for inviting me to this panel on media and drugs—a topic I am deeply passionate about. I have been working with journalists for two decades, so let’s delve into some insights around this. We begin with a concept cloud from a study among students at the University of Barcelona, focusing on the term “drug.” It reveals that even among the youth, the collective perception is laden with negative terms like “problems,” “addiction,” and “dependence.” This illustrates how societal views towards drugs and and those who use them are significantly shaped by media representation. Media coverage, as unanimously critiqued by journalists themselves, is problematic, being described as superficial, sensationalist, moralistic, and stigmatizing. So the first conclusion is that without any exception the reporting on drug information is a disaster. This criticism is so profound that some journalists admitted feeling ashamed for contributing to the prevailing negative narratives. The reasons cited include structural issues within the media landscape and personal factors/biases, pointing to a critical lack of specialization in drug-related reporting – which is also attributed to a lack of knowledge, the abuse of police sources, and the fear of dissenting from nationwide hegemonic discourses. Little has changed over the last century. Reflecting on the portrayal of drugs across history, from exaggerated newspaper articles in the early 20th century such as Time Magazines 1940 article depicting black men who use cocaine into “better shooters and more resistant to bullets”. Similarly, in modern depictions and discourse we have drugs turning individuals into ‘cannibal zombies,’ – it’s evident that sensationalism has been a constant. This not only pertains to news but extends to music, cinema, TV, and even presidential campaigns, often depicting drugs as invariably addictive and destructive. Looking back, propaganda has been a significant tool for shaping drug narratives, from the Motion Picture Production Code of the 1930s to the U.S. government’s deals with TV networks in the 2000s to include anti-drug messages in programming. In 2000, there was a notable instance involving multimillion-dollar agreements between the United States government and major television networks. The core of these deals was a proposal for the inclusion of anti-drug messages in TV programming. Under these arrangements, many popular shows were encouraged to incorporate anti-drug plots in exchange for government advertising subsidies. This initiative, however, was not widely publicized, and the agreements required that producers, writers, and actors could sometimes be asked to modify scripts to include messages that aligned with the government’s anti-drug campaign. As time passed the war on drugs continued, and the tools for media manipulation and propaganda evolved and becomes more subtle. This historical manipulation of media to control drug narratives has had a lasting impact on public perception and policy. Our study on media influence shows a direct correlation between media coverage and legislative changes regarding drugs, underscoring the potent effect of media and societal pressure on shaping drug policies. At the core of our discussion is the question of what policies we should implement to support marginalized populations, often dismissively referred to as “disposable.” Such demeaning language, alongside the imagery commonly used in news media, perpetuates stigma and criminalization against people who use drugs. It also fosters a culture of fear and rejection toward these individuals. A particular study examined how media coverage of certain substances influenced legislative changes. The research compiled instances of media coverage and analyzed the correlation between the portrayal of these substances and subsequent behavioral and policy changes. The findings suggest that political decisions are often swayed by media and social pressure, highlighting the significant influence of media on public opinion and legislative action. Interestingly, tools like Google Trends reveal how public interest spikes in response to media coverage of drug-related topics. For example, in the UK, searches for …(mephedrone/4-MMC )…surged following relevant news stories, indicating a direct impact on public awareness and concern. However, equating increased search volume with actual drug use or interest can be misleading and is not scientifically robust. The overarching theme is that the current narrative around drug use, fueled by sensationalist media coverage, may actually hinder efforts to address the issue effectively. It could be leading to the opposite of the intended effect. Therefore, it’s crucial to shift towards a more empathetic and informed discussion that focuses on support and rehabilitation rather than stigma and criminalization. This change in narrative is essential for creating policies that genuinely address the complexities of drug use and support those affected. Yet, there is hope in changing the narrative. Campaigns such as “Nice People Take Drugs” and “High Humans” have sought to challenge the prevailing media narrative by making visible the lived experiences of drug use, portraying it as a facet of reality rather than a deviation from it. These campaigns have been strategically placed in public spaces, such as bus stops, making them accessible for public viewing and challenging entrenched anti-drug norms. Documentaries like “Sybaritism” offer an alternative narrative, showcasing personal experiences that highlight the enhancement of sensory perceptions or the facilitation of social connections through drug use, rather than depicting drug use as an escape from reality. These narratives emphasise drug use as a means to augment reality, rather than detract from it. As we witness these shifts in narrative, it’s clear that a change is on the horizon. By challenging media perceptions and depictions of drug use, we open the door to more nuanced conversations and policies that reflect the complex reality of drug use, emphasising harm reduction and the human rights of those who use drugs. Through these efforts, we can hope to dismantle the propaganda that has long clouded public understanding and influenced policy in the realm of drug use. Thank you so much.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Thank you so much, Nuria, for another enriching presentation. Your insights on how imagery and representations contribute to the stigma and dehumanization of individuals are invaluable. You’ve opened up a discussion on the potential for change by moving away from conventional narratives about drugs to more nuanced, empathetic ways of storytelling. We are fortunate to have on our panel another individual with extensive experience in journalism, Johan. It would be particularly interesting to hear an insider’s perspective on the dynamics within press and editorial rooms. I’m eager to learn how you’ve navigated the shift away from the mainstream, hegemonic approach, and stigmatizing narratives towards the more compassionate approach that Nuria highlighted today

Johan Wicklen – reporter and author of “We will never give up”: I want to give you a quick background to my journey as a drug reporter and also explain why I think this job is important and what the future might bring. The subject is universal, but my focus will be Sweden. In short, two different developments sparked my professional interest in this subject. First, while working as a science reporter for the Swedish public service broadcasting company, SVT, I became more and more aware of the lack of evidence-based treatment for people that used drugs. It was obvious that harm reduction policies that other countries accepted were not, and historically had not been, spread in a proper manner. Talking to experts and reading up on the history of Swedish drug policy, it was obvious that morals had triumphed over practical and theoretical knowledge. The second was cannabis reform. When this started to happen for real around 2012, I decided this was something I had to follow. It seemed obvious that it was going to shake up a world where prohibition had been king for so long. But as a news reporter, you can never go deep enough to make people really understand the subject. Especially in Sweden, where I would argue that the knowledge about illegal drugs is extremely low while feelings about the same subject can be equally fiery. “Whereas Swedes are usually rational and calm, when drugs are discussed, rationality seems very distant and emotions get the upper hand”, as one of many outsiders studying the Swedish drug policy once noted. This was also something I noticed early and it intrigued me: The drug discussion had a tendency to make smart people dumb, and make usually calm people very emotional. That’s why I decided I needed to go back and not only tell the story about Swedish drug policy but also tell the story about why Swedes acted the way they did. This demanded a book. And that forced me to go much deeper than I had previously done as a news reporter. Something that gave me freedom and confidence to really start to ask the tough questions and also call out bullshit while still maintaining my journalistic integrity. I also wanted to spread knowledge about the subject to other journalists. This was really important for me, and the last chapter in my book is called “The Big Betrayal, a Manual in Drug Reporting”. I wanted to instigate a discussion about things like, why we as reporters should not let the police be the only source in a drug story, and also about different words that could be political and stigmatizing. Discussions that hopefully in the long run can make us better. In some ways though, I’m a bit pessimistic. Both drugs and crime are heavily discussed in Sweden at the moment, but does it lead to a drug policy debate? No. Instead, when the subject is being debated, the focus, as usual, is put on users. “Stop using drugs”, is the message. A very, very simplistic slogan to combat a very very complex problem. Although one with a long history in Sweden. The official police slogan in the late 80’s and early 90’s, for example, was simply: “It must be hard to be an addict”. And the roots go even deeper. The driving philosophy behind the Swedish vision about a drug-free society – decided in the 80s – was that drug supply was secondary, and demand was everything. The user was both the problem and the solution. Which in 1988 led to the criminalization of the use of illegal drugs. A law that still is in place today. But Sweden is not an isolated island anymore. Around us, things are happening at a rapid pace. In a world where prohibition has been king, people are exploring alternatives. We see countries experiment with different cannabis policies. We see politicians talking about regulating other drugs, such as cocaine. We see the topic of safe supply being discussed to combat the overdose crisis. Complex issues that cut through serious subjects like human rights, health, and security. And they deserve to be taken seriously. And that’s why it’s more important than ever to not only have knowledgeable journalists, but to have ones that really understand that prohibition is not a natural law. Not because you believe that legalization is better, but because if you are not open to exploring different alternatives, you are not unbiased. You are not doing your job. In a live radio interview right after my book came out, I got a question that read something like this: Is it a drug liberal book? Are you a drug liberal? My answer to that was: No! It’s a drug-neutral book, and I’m a drug-neutral journalist. And this should be the starting point. The very least we as journalists can do to give a more fair and balanced view on this serious and complex problem. Thank you.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Society will need time to reflect on the concept of being ‘drug neutral.’ It’s unusual for us to encounter a sense of neutrality or objectivity in media portrayals of drugs, even though we often consider these qualities fundamental to journalistic reporting. This rarity leaves us feeling somewhat adrift, especially in discussions related to drug policy, where a balanced and unbiased perspective seems crucial yet elusive. Earlier, we also heard from Paula about the vital role civil society organizations can play in ensuring accountability for media narratives. This point Paula made is intriguing, and I’m hopeful Dalel will further explore not only the role of civil society in pursuing accountability regarding these narratives but also their role as educators concerning them. Media narratives, particularly those that should be at the forefront of public discussion, are often complex and intersect various issues. Instituto RIA has been exemplary in tackling these challenging topics with both transparency and insight. It would be enlightening to hear more about your experiences in this area. And, let me express my gratitude for your presence with us this morning

Dalel Perez – Instituto RIA: In the discourse surrounding drug use, society often presents only two grim outcomes: prison or degradation. The narrative is riddled with inaccuracies and exaggerations—drugs kill, or one try and you’re hooked—messages that not only fail to resonate due to their fear-mongering nature but also perpetuate harmful stereotypes, especially against marginalised communities. This stigmatising language, particularly aimed at people of colour who use drugs, deepens the existing divides and further marginalises specific groups. Such fear-based tactics, while aiming to delay the age of first use as a harm reduction approach, often achieve the opposite. They make audiences sceptical of future messages, especially when teachers, who should be sources of objective information, only reinforce these stereotypes. In an age where students have access to a wealth of information online, continuing down this path of misinformation only undermines the credibility of educational efforts. Current drug policies cause more harm than good, necessitating urgent reforms. A better approach would focus on providing support services, objective information, and highlighting harm reduction, support, and even pleasure, rather than propagating fear and stigma. At Instituto RIA, we strive to foster honest conversations about actual drug experiences, engaging in the discussions people want to have and acknowledging the positive aspects of drug use. Our goal is to break down the myths that dominate the discourse and replace them with a more nuanced understanding. Women who use drugs, in particular, find themselves obscured behind stereotypes, lacking access to scientific literature to make informed decisions. Our research has shown that women’s needs, especially concerning pregnancy, menopause and breastfeeding, are not being adequately addressed. There’s a dire need for non-judgmental dialogue on these topics, ensuring women are not kept in the dark. To truly meet the needs of all drug users, we must design gender-specific programs and policies that stem from empathy and compassion rather than fear and stigma. Peer work has emerged as a crucial element in facilitating conversations about lived experiences and the autonomy of people who use drugs (PWUD), emphasising that each individual is the expert on their own use, not healthcare providers. In drug checking services, providing information through horizontal interactions empowers the service user, reinforcing the importance of treating individuals as equals. As a civil society organisation, we remain committed to producing evidence based on human rights, risk reduction, advocating for social justice and peace building, and transforming narratives to focus on people instead of substances. Our research indicates that most people have positive experiences with drugs. It’s time to stop underestimating people’s intelligence and their capacity for agency and autonomy. By shifting the narrative and employing a more empathetic and evidence-based approach, we can begin to dismantle the stigma surrounding drug use, advocating for a society that values honest dialogue, social justice, and the well-being of all its members.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Thank you so much for that Dalel. I retained the idea of the connectedness between sort of politics and policies, narratives and services and how policies, narratives and services can be put at the service of life and rights. And another thing that I returned from the last presentation is the very material impacts that these narratives and these laws have on people’s lives. I’m very privileged to have with us Gloria Miranda, from the directorate for drug policy of the Ministry of Justice of Colombia, because the recent national drug strategy by the Government of Colombia is precisely about life about sowing life, which is an expression that I absolutely adore so it would be fantastic to hear from glory about what the, what’s the approach in relation to this issue of the Government of Colombia.

Gloria Miranda – The Directorate for Drug Policy, Ministry of Justice of Colombia: Thank you to Instituto RIA, for having me here. Good morning, everyone. Colombia’s national drug policies, are the first drug policy in the world that recognises openly the failure of the war on drugs. So we as a government understand that the war, rather than against drugs, must be against poverty, exclusion, inequality, and violence. So this policy was the result of a broad process of dialogue and participation from civil society, especially from the communities of the country of the territories that has been most affected by the war on drugs and by the illicit drug trafficking. Today, they are at the centre of the national drug policy ‘So in Life.’ So it would mean what means ‘so in life’ it’s essentially like rethinking rethinking the drug phenomenon and challenging stigmatising narratives. Different needs and narratives have been generated around the drug phenomenon that have translated into practices of stigmatisation, criminalization, discrimination, and violence. So these have certainly undermined the rights of the groups mostly affected by illegal drug markets and by the war on drugs, but as I said before, they are now at the like the centre of our drug policy. So, these contexts have been very unfortunate for Colombia since all these stigmatising narratives have translated into poor populations, for example, to cultivate illicit crops for their subsistence or mother head of household who has had to distribute small amounts of drugs to feed their children. They have been labelled as criminals, as drug traffickers, and the other is people who use drugs. So they have suffered such as stigmatisation through terms as as you said Nuria and Paola said, ‘drug addicts,’ ‘junkies’ or ‘derelict’, and these has been like accentuated by public discussion on some media strategies. So they have linked drug consumption with disease, crime, and violence without exception. This is not supported by evidence, I think this is the worst part. And due to these prejudices surrounding psychoactive substances consumption I have like some information. For example, 53 percent of Colombians do not want to have neighbours who use psychoactive substances. And in addition, exclusion and self-exclusion from consumers itself from the right to have a family, to have education, to access to health. Some of them prefer not to access to care treatment services, because they prefer not to be stigmatised. And the worst of all, I think, to close this broad context is that the stigmatising narratives have perpetrated strategies that have been proven to be ineffective, such as prohibition. So, the I think the main example is increasing penalties for carrying small quantities of drugs. These has not protected rights. And has not improved the quality of life of anyone; these have just like continued to vulnerable the rights of people. So this is why the change of narratives is one of the like the axes of the drug policy of Colombia. We have eight axes; one of them is change of narratives, because we can’t implement the other strategies if we do not change narratives. For example, of we as authorities of the government still see consumers as ‘sick people’ or as ‘criminals’, we can’t have drug policies based on public health. A big example of this is our senate rejecting for three or four…I don’t remember… consecutive times the bill to regulate cannabis. Also, mayors in big cities or in main cities have prohibited consumption of substances instead of providing safe places to consume substances, especially for vulnerable people. So to close my intervention, our National Drug Policy conceives of strategies including the use of cultural and artistic tools; for us, it is fundamental to promote an informed understanding of the drug phenomenon. So we are using tools like cinema, museum exhibitions, and supporting civil society organisations. We recognise the huge work of Elementa around detoxifying narratives. We are also using pedagogical activities, social dialogue, memory. It’s very important and we are also working with communities, civil society organisations, and private sector because as I said before, if we do not change narratives, if we do not change our understanding of this, we cannot have a new drug policy. It’s impossible if we do not change mindsets. We cannot implement a drug policy based on human rights nor in public health, or gender or anything new that we want to implement. So for us, this is like the first step.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: In our discussion on challenging media perceptions and depictions of drug use, the concept of narratives stands out as a cornerstone for the change we seek. Although we are closely aligned with our scheduled conclusion—and acknowledging our slightly delayed start—I want to seize this moment to invite Dr, Gady Zabicky, who joins us today, to share some closing thoughts. Mexico’s keen interest in this topic underlines the importance of hearing from diverse perspectives. Dr. Zabicky, the floor is yours for some brief concluding remarks.

Dr. Gady Zabicky: I was walking my dog, I stumbled upon a scene that really made me think. A grandma warned her kid about a guy smoking a joint nearby. He responded, “We’re just chilling, not causing trouble.” This moment stuck with me, highlighting how quickly we jump to stigmatise drug users. This reflection led me back to a campaign called “Nice People Use Drugs,” started by a friend of mine, Sebastian Saville. Despite its aim to challenge how we see drug users, it faced backlash and calls for removal, proving just how taboo this topic still is. As a doctor who’s moved into advocating for drug rights and medical cannabis, I’ve seen the arts, sciences, and humanities collide. But diving into public service opened my eyes to the real struggle of changing drug policy narratives. We tried to address the whole spectrum of drug prevention for Mexico’s diverse population, from those who’ve never touched a drug to those needing help. I’m sharing some behind-the-scenes insights here. Changing the narrative isn’t just about big campaigns; it’s about everyday conversations and challenging stereotypes, one step at a time. Through my experiences, especially transitioning into a public service role, I’ve learned that governmental efforts in drug policy are not as straightforward as one might hope. Addressing drug use among Mexico’s diverse population of 130 million requires a nuanced approach. We have mothers unfamiliar with any drugs, necessitating selective prevention focusing on higher-risk individuals, and indicated prevention targeting those already experiencing health issues due to drug use.On the other hand, the notion of legalising everything, for instance, is considered too polarising and unlikely to garner widespread support. From a governmental viewpoint, pushing for narrative change can be a double-edged sword; presenting too radical a message might backfire. Drawing inspiration from the history of modern medicine, where the understanding of how veins function was initially met with scepticism, the strategy wasn’t to confront detractors directly. Instead, by demonstrating through experiments with animals, the scientist subtly shifted the narrative, using the force of opposition to bolster his discoveries. This story serves as a reminder of the delicate balance required in advocating for drug policy reform. Civil society’s role in this discourse hasn’t always been viewed favourably. As the Japanese proverb goes, “If one nail sticks out on the table, it receives the full force of the hammer.” This analogy highlights the challenges faced by those daring to challenge the status quo in drug policy. However, it’s crucial to recognize the emergence of a new generation openly discussing their experiences with psychoactive substances. In navigating the discourse on drugs, we find ourselves at a crossroads where the voices of the past intersect with the aspirations of the future. As we push for change, let us remember the importance of strategic communication, leveraging our collective experiences, and fostering an environment where informed, compassionate discussions about drug use and policy can flourish. This journey is not without its obstacles, but with courage, empathy, and a commitment to evidence-based practices, we can work towards a more understanding and just approach to drug policy.

Chair – Juan Fernandez – IDPC: Thanks everyone, this brings us to the end of our side event. Thanks again to the panel members and all of those who’ve attended