Chair, Singapore: We’ve seen that unilateralism didn’t work and there was a turn to multilateralism. The Commission was then pushed by various activists that led to the signing of the Opium Convention, the first internationally binding agreement that was the basis for the current drug control conventions. Tomorrow is the 55th anniversary of our first drug convention, which is the foundation of international solidarity and signals a well-functioning system to control precursor chemicals. There are pressing challenges however – we see a diversifying market, for instance. The debate between prohibition and regulation is intensifying. Today’s panel was meant to be an opportunity to have a candid discussion about where we are and where we are going within the global drug control regime.

Mr. Joncheere, INCB: Thank you for the side event on this challenging subject. The Treaties were elaborated to respond to widespread public concerns, specifically in relation to opium. The global drug situation is as complex today as it was at the signing of the Treaties. At the time, largely plant-based drug situation; today looks at more chemicals that can be manufactured in many various ways. At the time of their drafting, the Conventions were worded in a way that covers the diverse legal systems of the members. It was meant to be flexible to adapt to the changing landscape of the drugs situation. States have realized the need for concerted action in the field of drug control and based in common and shared responsibility. INCB has developed a set of programmes to help countries deal with the scourge of NPS. We also facilitated the shift from purely criminal justice responses to those that focus on due process and are based on human rights. Capital punishment has been abolished by many states, extrajudicial measures that are clearly not in line of the conventions have continued to be practiced. The Board has spoken out about it many times. The conventions don’t require absolute prohibition and don’t require punitive responses – the Conventions explicitly provided space for alternatives to incarceration. Implementations on the national level are diverse. The Ministerial Declaration this year has helped MS balance humane and balanced policies based on human rights principles. The underpinning of the Treaties is limiting availability of controlled substances to medical and scientific use. Some countries have adopted measures that are not compatible with this, especially regarding cannabis. The Board has spoken out about the issue and engaged in dialogue with affected states. The INCB is mandated to monitor compliance, the legal obligations are owed to each State party. Ratifications are legally binding to the signatory countries, regardless of their local political structures. Legislative measures that counter the conventions pose a serious challenge and require further discussion. Another important challenge to promote the health and welfare of human life is the continued unavailability of controlled substances in some countries the inflict unnecessary human suffering. In the world, where some people seriously lack access to pain management, it is ironic that other areas are suffering from the consequences of over-prescription. The drug control conventions continue to be relevant today, the ultimate success rests on the willingness of State parties to fully implement the measures in a way that’s sufficiently resourced and respects human rights. In the spirit of respect, great benefits can be gained when countries come together and put individuals at the centre of their policies.

Ms. Yanchun, China: Years ago, our forerunners acknowledged that no country could win against the opium issue alone. The following century was a long way to produce results in controlling the spread of drugs. China has always attached great importance to the drug control issue, we have successfully tamed the growth in the number of drug addicts. Recently, some countries have come to a view that the drug problem should be dealt with differently. The international community remains optimistic, to strengthen our work countering the drug problem, upholding the 3 major international drug control conventions as cornerstones to international drug control – no system can be perfect, but we call on Member States to explore legislative options and better use the flexibility of the conventions to implement the measures locally (we scheduled fentanyl analogues for example); we respect the rights of countries to adopt measures that respond to their national specificities but we refuse the reduction of harm as an excuse to legalise drugs – a balance should be struck with defending human rights and upholding the regulations; innovation and response to new challenges – we cannot be outsmarted by evil; control drug manufacturing equipment; co-ordinate efforts to increase measures addressing drug production – as a result of increased crackdown, price of illegal drugs have increased [specifically in opposition to Australia and New Zealand]. We call on the international community to pay more attention to the Golden Triangle. From a Chinese global perspective, all countries should show responsibility and march towards a new consensus.

Mr. Lemahieu, UNODC: Since the first Opium Convention, the international control system continued to build layer on top of layer to perpetually renew itself. So, what is global drug policy goes beyond those three Conventions – there have been a number of declarations, resolutions, segments that approved the system. It has always been a dynamic process, building on the past and adjusting to the present. 5 variables that ensure the smooth working of the global drug control system: (1) evolving body of evidence, (2) narratives we build around evidence [and reflecting around political intentions], (3) history, (4) context, (5) forecasting future challenges.

[…reference to Nixon…] substantial federal reserves were directed towards preventing growing the number of addicts. The first “war on drugs” had a different aim; the forced opening of Chinese borders meant serious British imports of opium. The devastating impact of the spread of addiction … [historical context]. We used to have specific countries that served as production, transit and consumer – it looks very different today. More humane approaches have been tested, accompanying the conventions, it is a continuing evolution. History matters. Different volumes of drugs are circling in South America and Asia – the accompanying violence is different and [the degree of] their link to the illicit drug market is also different. Effective prevention is an absolute priority – how can we stigmatise a drug and not use it? Oversupply of narcotics while not making advances in ensuring medical access is a problem. This lack is often rooted in the domestic context.

Successful drug control is flexible, agile, inspired by history, adjusted to context, looking into the future, represents cross-border solidarity and respect, a give-and-take. Preventing suffering, ensuring access to medicines; protecting the rights of individuals to be free from drug dependence.

Ms. Prugh, United States: USA has found itself as a leading country as far as challenges go. While we face them, the real scope of our problem is not well-understood. We are now facing a major opioid crisis, that is our problem. In terms of cannabis, we have a public relations problem. There are headlines about states legalising Cannabis but as a federal government, our obligations to the treaties are undertaken. We have the Controlled Substances Act, which applies throughout the United States and our territories. How can this be if you have state laws run one way and federal laws going the other? Our domestic structure is different from the European Union. We ratify our convention while we allow our states to retain some of their sovereignty. Amendments that protect human rights are dear to us, the 10th amendment ensures that certain rights are reserved for the states. So, our federal government binds itself to the conventions while the states regulate within their location – those are only applicable within state borders. My home state, California plays a leading role in this “independent” thinking. The federal decision was that there is no medical use for cannabis. We did recognise some medical utility in the case of some medicines that derive substances from the cannabis plant. Medical usage of cannabis is not prohibited under the Conventions. On the federal level, we never recognised medical use and so states making those regulations contravene federal law. Anyone engaging in activities that are federally illegal can be federally prosecuted. We look at the 1988 Convention with trepidation – this addresses the proceeds of crime. Based on this, federal government has restricted access to the banking system for those who are not pursuant to federal laws. We are seeing a by-product: organised crime. We haven’t figured out how to thread the needle here – addressing this mentioned problem and remaining faithful to the Conventions.

We are not permitted to flexibly interpret the Conventions; they are highly respectful of state constitutions. There is a clause in the Single Convention, article 39. We have to be cautious about simplifying the Conventions. The States are the entities that are responsible for interpreting and applying the conventions. CND is a treaty body with responsibility to give guidance to other states in interpretation, we can also rely on INCB and CND but ultimately, it is our responsibility. Let’s undertake our charge seriously and effectively. This is our common and shared responsibility.

Dr. Rimner, Utrecht University: I do not represent the views of any delegation. I am not even a diplomat, so I am asking you to take into consideration the long-term view.

The core phase of mobilisation against the opium trade was the largest State-sponsored trade. The League of Nations can be described as a period of convergence – as well as social and political concerns. The two opium wars saw a push for prohibition by civil society prompted by States doing too little to guard health. This led to the introduction of public health as a concept in [policy making]. Diverging interests were made compatible through political means. This is the basis of today’s international drug control system.

Interests in East Asia and “the West” became compatible with imperialism left off the papers. Criminalisation entered legislative bodies as a reaction to the opium wars. At the time is was considered that demand was a function of supply, so efforts addressed supply. The conversion of interests had several reasons: China saw a link between drug and human trafficking, fiscal interests were identified, state sponsored trafficking became a prestige issue. Today is different from the late 19th century: even with the golden triangle, Asia doesn’t serve the same purpose in drug production and trafficking; early legislations didn’t have political intentions. Lessons of history: Shield the regime of global drug control from wider political forces. Will it be possible today by building societal support for drug control measures and building coalitions?

Jamie Bridge, Vienna NGO Committee:

Presentation in PDF available here.

Fantastic to see so many state sponsors for this event. I would like to talk to you about the role of civil society in the process. [VNGOC intro]

Brief History of Civil Society Involvement:

1946: The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) established

1954: 6 NGO representatives attended the 9th CND

1983: VNGOC is established

1984: NYNGOC is established

1986/1987: NGO Forums linked to International Conference on Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking (1998: UNGASS provided new levels of CS access (NGO Village)

2006: CND resolution on civil society participation (49/2)

Beyond 2008 Initiative: Over 500 NGOs from 116 countries; 9 regional consultations; Global Forum with 300 NGO representatives; Declaration and three resolutions adopted by consensus.

2014: Civil Society Task Force (CSTF) launched for the UNGASS

2015: Global and regional consultations

2016: UNGASS: 11 CS speakers and “contributions” from ~60 NGOs

2018: CSTF relaunched for the Ministerial Segment -> Global survey (~500 NGOs)

2019: Civil society hearings in Vienna and New York: Conference Room Paper submitted

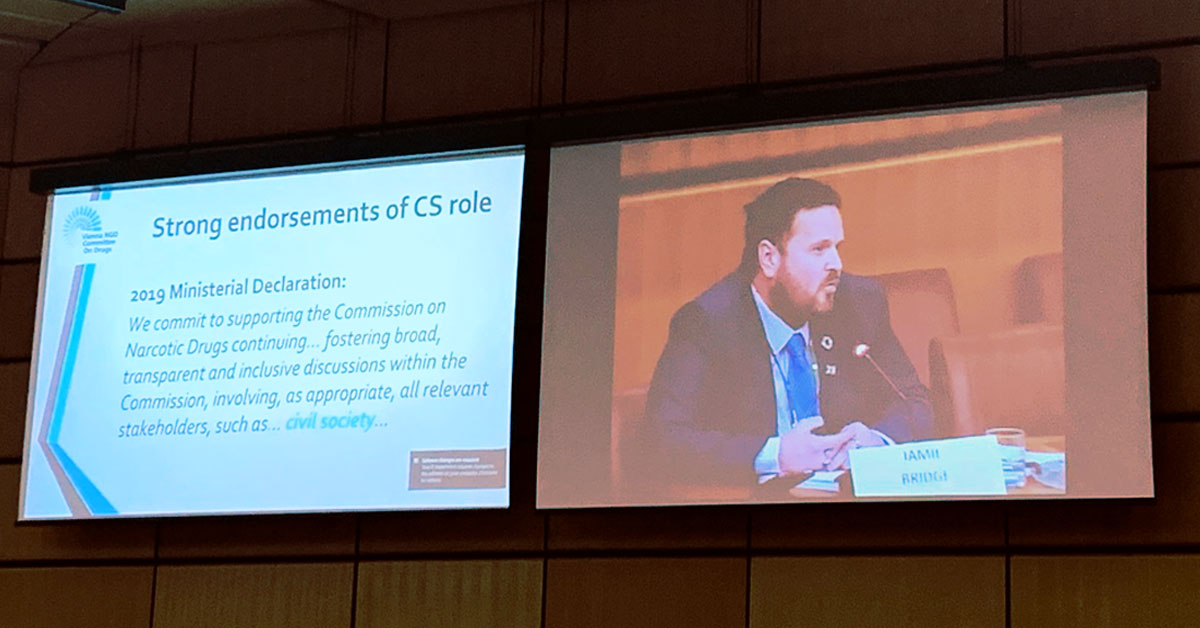

Recently, there have been strong endorsements of the role of civil society within key policy documents such as the UNGASS Outcome Document, the UN System Common Position on drugs and the 2019 Ministerial Declaration. ECOSOC-registered NGOs are “observers” – but can attend all public meetings, apply to make oral interventions in the main session, organise and participate in side events, submit written and video contributions. We’ve seen an increased NGO representation in government delegations: Our voice is being heard – Thank you!

Chair, Singapore: We’ll take a few questions from the floor now.

Mexico: We decided to co-sponsor this event because we saw this as an opportunity for consultation, including civil society. We look forward to further events like this.

Pakistan: Happy to co-sponsor. We’ve been having a debate saying prohibition doesn’t work and we should try a more liberal approach, but an important gap is the implementing capacity of the State – we see drug mafia getting smarter and stronger than our authorities. In regions like ours, with more than 60% of youth and high population density, how can we increase our capacity? How can we make better use of innovations?

Canada: We welcome the effort to identify innovative approaches. We support the drug control conventions; we remain committed to reach their aims – we promote evidence based solutions to achieve health and safety for all humankind.

Malaysia: We see delegations divided into two blocks. How can we go forward with these differences?

International Association for Hospice & Palliative Care (IAHPC): Lack of access to medicines, one of the Treaty obligations, why is this needle so stuck? The narrative has improved, the UNGASS outcome even had a chapter on it but on the ground, there hasn’t been much actual change or implementation seen.

Nepal: Looking at media and opinion of civil society, CND is sitting on the cannabis decision. How can we address this public relations issue? The CND has always been open to CSOs, as Mr. Bridge has said so.

Mr. Lemahieu, UNODC: Malaysia asked a very good question, but it is very open… overall drug control has been working with a declining budget. Many countries have little public revenue and a small public health budget. We are looking for more international support.

Mr. Jocheere, INCB: How do you quantify a set of international commitments with the changing environment around us. INCB has a special role within the system and we are keen on bringing evidence together and look at innovative approaches. In terms of access, not enough progress is a great frustration, but it is a multifaceted issue: narratives, domestic budgets and intentions. Our next step would be mobilising resources. Let’s hope that when we put that on the table here, there will be a push in the right direction.

Russia: We believe we should distinguish legal and political framework – as Jean Luc said. Obligations from MS are not mixed with political intentions: Full and effective implementation of the conventions! INCB plays an important role in strengthening MS’s capacity to implement the conventions, eg. they held a learning program in Moscow earlier in December this year. The US delegation had sent a strong legal expert on this panel, we know US puts a specific emphasis on countering drug trafficking – what are the justification for actions outside of US jurisdictions.

Ms Prugh, United States: The INCB’s role is to aid Member States; they are not enforcers, their mandate is not to oversee implementation. Our treaty is focused on achieving the desired outcome which includes availability for scientific and medical purposes. Regarding your question, I believe you are referencing suspected drug trafficking vessels on open seas – we get approval of the origin country before boarding those vehicles. These are real time operations targeting drugs or human trafficking. We usually get an expeditious response, often there is acknowledgement of the vessels but no response from origin countries. Our attempt was to raise this issue – trafficking on high seas covers 85% of global drug trafficking.

Chair, Singapore: We have national history on sea trafficking. I don’t want to summarise today or draw any conclusions as our main point today was the value of doing events such as today’s. We aim to have a nuanced dialogue about relevant issues and recognising the overall support for an international drug control regime. There is debate around the architecture of the system but as was the case with opium back in the days, nobody can deal with the drug problem alone. The work is cut out for CND but let us not forget the sovereign power of States and the important knowledge and expertise of civil society. We have different perspectives and specific challenges, but the current framework has been serving us and is a useful tool for our collaborations. Thank you very much for joining us today.